Bruce LaBruce has been at the forefront of Queer underground art and cinema since he started making short films in 1987. After releasing two feature films, he secured his status as a cult icon and adjacent to peers such as Richard Kern, Kembra Pfahler and NYCs Cinema of Transgression.

Bruce LaBruce has been at the forefront of Queer underground art and cinema since he started making short films in 1987. After releasing two feature films, he secured his status as a cult icon and adjacent to peers such as Richard Kern, Kembra Pfahler and NYCs Cinema of Transgression.

However, it was LaBruce’s 1996 film Hustler White that brought him universal acclaim and a notorious reputation as a shit-disturber of the status quo. The noteriety found him positioned amongst the likes of Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, Gregg Araki and the so-called New Queer Cinema movement. It also landed him a curse cast on him by the witchy queer film forefather Kenneth Anger for referencing him in the film.

Labruce has since forayed into work as a highly regarded writer, photographer, and reluctantly (as the title of his 1997 memoir would have you believe) pornography.

Since his debut feature, 1991’s No Skin Off My Ass, LaBruce has helmed thirteen feature films and as many or more shorts films. However transgressive LaBruce’s work may be, there’s a sentimentality and tenderness that runs through his narratives, just as tangibly as his punk inclinations do, creating a sensibility that can only be referred to as LaBrucian.

Emerging from Toronto’s 1980s punk scene, LaBruce gained initial notoriety and cult-god status with his pioneering queer punk zine J.D.s — a collaborative effort with artist and filmmaker G.B. Jones. The zine was a confrontational and exploitation response to the homophobia the two had encountered in the punk scene, and snowballed into a web of freaks and outsider gays across North America and beyond, eventually being dubbed the “Queercore” movement.

Despite its subversive origins, the legend of Queercore and J.D.s has since been been exploited into quasi-mainstream status, as seen in such recent articles in Teen Vogue, and even being hilariously, yet disastrously referenced by major fashion houses such as Gucci.

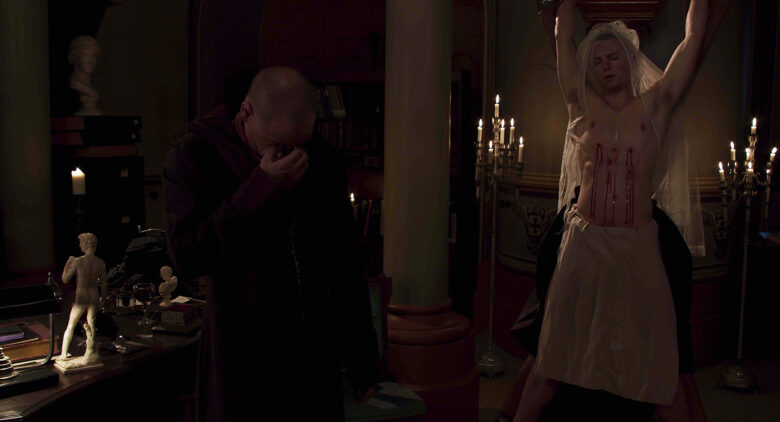

While still making the rounds in the festival circuit, his thirteenth feature film, Saint-Narcisse, was released to critical acclaim at The Venice Film Festival in a brief window between COVID lockdowns in 2020. The reliably scandalous film is being referred to as his “opus” and is finally reaching audiences via theatrical runs in Toronto, Vancouver and more to come, after being held over for weeks at the Quad Cinema in New York City.

The story of Saint-Narcisse centers around a brother’s quest to uncover the dark truths about his family’s past, and finds him in an erotic tryst with the twin brother he didn’t know existed. The film blends LaBruce’s inclination to find believable and affecting relationships between unconventional characters with his seemingly insatiable urge to disrupt.

The last time OMG.BLOG spoke to Bruce was in 2008. This time around, we talked with him about the influences behind his most recent film, his storied career, and why we shouldn’t expect him to go PG anytime soon, despite his best efforts.

Read the full Q&A and watch the trailer for Saint-Narcisse after the jump!

�

Hi, Bruce! How does it feel to finally have audiences outside the festival circuit get to see your new film, Saint-Narcisse?

It’s really amazing and kind of miraculous that the film is even getting a theatrical distribution in a way, because there’s such a big backlog of films after the pandemic and everyone’s trying to get into theaters. So, I’m really happy that it having a theatrical release in both Canada and the U.S.. I was in Los Angeles a couple of weeks ago, and it was amazing because I hadn’t been to LA in three years or something.

It gave me a chance to hang out with a lot of old friends and go to clubs and restaurants and just have fun. Now I’m in New York for the first time since before the pandemic and I plan on doing the same thing, just seeing friends and viewing my marvelous movie! So it’s a win-win!

Do those cities feel re-energized to you, or are our collective standards just lowered?

Well, I don’t know. I have no standards, really!

Would you still care to make movies if the element of in-person screenings was no longer a thing?

Well, I’m having an existential crisis about filmmaking in general. Like everyone else, I’m questioning the relevance of the idea of cinema as we once knew it. I’m completely resistant to the Netflix-ification of movies. It’s not just about showing films in the theater, it’s about how the films are made, and who’s making the films.

It’s no longer a director’s medium, it’s more of a producer, show-writer or runner’s medium. Actors have started taking over in terms of like directing as well. Everything is so cookie-cutter in a way. I actually just cancelled my Netflix membership. If you look at it from a critical eye — and critics don’t have a critical eye anymore — its like they’ll heap praise on anything. It’s partly to do with the homogenization of the digital of takeover of cinema.

It’s really ingrained in the way that things are shot, and the clichés of certain camera angles or the visual motifs that you see repeated over and over again. Obviously there are great things that are made even within that system, but that’s something that I totally resist.

I hate that there’s no formal intervention anymore, that there’s no kind of experimentation or attempt to revolutionize form in terms of narrative cinema. It’s as if Godard and the French New Wave never even existed.

How much of your interest in being a filmmaker involves around the experience of receiving praise in person?

That’s becoming increasingly irrelevant, not only in terms of cinema, but in terms of life in general. There’s a whole new generation who aren’t comfortable with direct social interaction or even with people. Lots of people would rather just do a Zoom premiere than go to a cinema. It’s the way the whole culture has developed in the social media age.

I’m obviously old school, so I still enjoy that kinetic spark you get from an audience or even the confrontations! I’m so used to making films that are confrontational and offend people. I had to learn how to defend my films in a public forum. When someone’s yelling at you in person in a room it’s different from fielding criticism online, which is usually just from haters and social justice warriors, which I don’t really care about, anyway.

But, if someone genuinely takes issue with your film and you have to defend it in person, there’s usually a process of a debate; it’s almost a conciliatory back-and-forth where you try to win the person over to your point of view or you get to the point where you agree to disagree. It’s a kind of a back-and-forth that you don’t get in the virtual world.

Also: just the applause. I mean, if you’re an old showbiz whore like myself, just having the applause at the end of the film doesn’t hurt. Saint-Narcisse got a standing ovation when it premiered in Venice!

I still think movies should be shown in cinemas. Saint-Narcisse is so gorgeously shot by the legendary Quebecois cinematographer Michel LaVeaux, it begs to be seen on the big screen. It just looks so beautiful, and there are so many little details and flourishes in the film that I feel get lost on small screens.

Was there a large amount of time between completion of the film and it being screened? Was the momentum of the project interrupted or beaten down because of the pandemic?

We were lucky to see it launched in person at the premier in Venice before everything really shut down. That made a big difference psychologically in terms of the payoff. You work like a dog to make a film; it’s a long arduous marathon. I got the idea for this film in 2013, and started writing in 2015 or so, so it took five years from writing to completion.

That’s a long chunk of your life, and many times during the writing process I almost gave up on it. Then we shot a film that should be shot in 28 days in 22 days, and it was a huge challenge for me. It was my biggest budget and I was working with a union crew and all that, which is not the usual way I’ve made films in the past, other than Gerontophilia.

I’m more of a guerrilla filmmaker, so there were many challenges beyond COVID.

Is it weird working with a straight lead actor? Though I guess the star of Saint-Narcisse, Felix Antoine Duval, didn’t have to do anything too gay, since he’s just making out with himself…

Yes, he does! He makes out with a body double!

Oh right….well there’s a large ensemble of presumably straight actors in the film. Is it strange trying to chorale a group like that into these sexually charged scenes?

No, not exactly. In terms of nudity and stuff, we had about thirteen extras, and we basically asked all the extras who would be comfortable doing that kind of thing, and I guess some were more willing to do it than others. The film is like my homage to Quebecois cinema in the ’70s, and nudity was so common back then.

As a child, I was hugely influenced by movies on CBC [Canadian Broadcasting Corporation] that showed these films with psychosexual plots and a lot of films from that era were all about family secrets, ghosts from the past, incest, and even like weird rape-type stuff.

The Act Of The Heart, in particular, was a huge influence on me, and, again, I saw this as a kid… Donald Sutherland plays a priest and he has sex with Geneviève Bujold, on the alter of the church. And then, Bujold goes to the park and souses herself with gasoline and sets herself on fire as the credits roll!

You can’t imagine what kind of effect that had on me when I saw it when I was just twelve or thirteen.

Well, I think anyone familiar with your oeuvre would definitely be able to imagine how it affected you. A lot of these cinematic explorations are cancellable in today’s age. How does an artist such as yourself navigate these tricky concepts in a sanitized era?

I happen to believe that we’re in a very regressive point in history. There are a lot of great, progressive things happening because of woke culture — like women and BIPOC being recognized as talented directors and also just in terms of representation, which is essential in this day and age.

But, on the other hand, I think we’re in a sexually regressive mode. I think there’s a puritanism and a lot of moral police.There’s this complete asexuality in this world of Disney or Marvel and DC comic movies. Sex is really unfashionable in a way right now.

I recently watched Fellini’s Casanova, which was made in 1976 and also starred Donald Sutherland, and this film is deeply adult. It’s a profound investigation of masculinity, and a demystification and deconstruction of masculine sexual authority. It’s a full-on philosophical treatise on sex and aging and the history of sex. There are no films for adults anymore that are literary, philosophical or psychoanalytic. Everything now is so infantile and entirely about appealing to tweens.

I’m just tired of the films now that reduced to this trite pop psychology about family dynamics that always seem to be about achieving the approval of the father or something. It’s just this glossed over representation of the family, of sex, or politics and everything.

So, what I was doing with Saint-Narcisse, in a way, was get back to that, because it was set in the ’70s and it was an homage to these films that played so much with the idea’s of family romance, and the sexual tensions within the nuclear family.

There’s a philosophical thread that runs through your entire career and the urge to explore taboos in unconventional relationships. In Skin Gang you have this liberal interracial couple who, especially at that time, should be a very good representation of progress in the gay community, but instead you go on to attack them…

I wouldn’t say attack. Critique.

Well they do get sort of… gang… How should we put this…

Oh right.

Like they do get attacked by a gang of skinheads… anally. But the critique lay more in the fact that, as a society, this bourgeois, sanitized, homonormative lifestyle is and was considered so covetable. In the opening scene your character gets gay-bashed by skinheads in an almost comical way… How do you find a way to navigate these themes with your trademark sense of humour?

I don’t know if I’d call that scene comedic, but it’s about sexual ambivalence. As a filmmaker, I have always acknowledged my sexual attraction and even fixation on these politically incorrect figures, authoritarian, or even fascist figures, which is built into a lot of gay cinema from anyone from Kenneth Anger to Mishima and of course, Fassbinder.

It’s an acknowledgement of the relationship between homosexuality, classism, and the sexualization of power and dominance. Look at Tom of Finland. If you’re not acknowledging that deeply embedded history, you’re just glossing things over.

In Skin Flick, we’re talking about a gay, mixed-race, middle-class couple, and, for that reason, they automatically have to be portrayed according to these censorship rules in an exclusively positive light. There can’t be anything sinister or complex or ambiguous about what they’re doing at all.

So, not only do I critique the bourgeoisie couple, but in a way, I encourage a certain kind of identification with the neo-Nazis skinheads who have certain qualities that are, almost… humanizing in way. They have male bonding, they have loyalty, and they have camaraderie and tenderness.

I do the same thing with the gay priest in Saint-Narcisse, who’s been sexually exploiting one of the twins. He ends up being like a classic cinema monster at the end, and he is punished for his sins, but, I also portray that relationship between him and the twin Daniel as a kind of Stockholm Syndrome relationship, which is a phenomenon where someone who’s actually exploited over the years develops feelings for their exploiter.

They become almost like a domesticated couple in the film, which is disturbing. I’m not interested in these films that are only interested in presenting gays in an exclusively positive light.

You’re a gay filmmaker who has a habit of casting gay characters as the antagonist rather than the protagonist in your films, and you reintroduce that element with the priest in Saint-Narcisse, who is a pedophile and a psychopath. Can you talk a bit more about exploring those rather topical tropes in this film?

The priest is probably the only completely gay character in the film! Everyone else is sort of bisexual or polyamorous, you know? But how can you represent a Catholic priest as anything but, I mean, with the whole history of the Catholic church and the fact that enforced vows of celibacy actually encouraged the sexual exploitation of boys and girls?

How can you not present that character in that kind of light? On the other hand, he’s like the father figure: he’s the superego.

How do you find balance in your work amidst this contemporary obsession with inclusivity and the seemingly long-perished idea of otherness that was inherent in gay culture?

Well, I don’t, because I still believe that the oppressed have become the oppressors. I mean, It’s a very common phenomenon. I honestly still think that about the gay community.

When you see the super Christian, “gay” American politician, Pete Buttplug or whatever his name is, who’s just barely a democrat with his monogamous husband with whom he just adopted twins. It’s like… What is the point of them? Why are they in need of representation?

Maybe their twins will have sex!

They represent the erasure of the gay identity. I’ve always been anti-gay as well. I’m ambivalent about it. The term “gay” just seems like such an outmoded idea that doesn’t even mean anything anymore. On the other hand, I’m so happy that I lived through the whole pre- and post-liberation era. I got to experience the excitement and the kind of power of gay sexuality emerging and militant sexuality being the engine of gay liberation.

There was nothing like it; it was pure liberation. It was like breaking out of a kind of sexual repression and monogamy and stale family values and all this kind of stuff that still keeps everyone domesticated and repressed. So, I’m glad I experienced both, but it gets complicated for me because I’ve always been sort of ambivalent about my gay identity.

I’m very pro-faggot. In the ’80s, I was always against the conformity of middle-class gay white, and the whole focus of the mainstream gay movement as often being sexist and racist. That was the whole idea of Queercore and what my zine J.D.s was totally about. It was about rejecting that traditional idea of what it meant to be a gay man or lesbian or whatever.

I have to admit, we were woke, like, twenty years ago. Teen Vogue recently did a piece where they talk about GB and I, and how we were way ahead of our time in terms of inclusivity, except we identified more with the outsiders who were more of the criminal… Well, the disenfranchised, minorities, etc.

Well you do explore homonormative relationships to some extent in your work, in Gerontophila, for example. That’s a fairly wholesome tale of love and longing, don’t you think?

It ends up that way, but it starts out that he has sex with other old men at the beginning, and at the end it’s implied that he’s going to go after old men again. So in a weird way, it’s a reverse Lolita.

If you look at it from a jaundiced eye, you could almost see Lake, the younger main character as a kind of predator, you know, but I always humanize people with fetishes, people with these queer desires that don’t fit into the mainstream — and intergenerational sex is still one of the biggest types of taboos, especially intergenerational romance.

It’s such a parochial way of looking at love and romance.

Does self-censorship impede your writing process at this point, given the nature of the themes you explore in your work?

At the height of the Me Too purge, which was very necessary to have happen, and the height of wokeness and political correctness, I really found myself for the first time on Twitter, for example, really censoring myself, almost to the point where I stopped tweeting. It was such a minefield that anything you say could blow up or be misinterpreted, or they won’t get the joke or whatever.

But, there has been a kind of backlash against woke absolutism, the intransigence, and looking at things only in a black-and-white way and not recognizing any nuance and policing desire, language, and sexuality.

For someone whose work is largely about provocation, it should, in theory, make it easier to for you to ruffle feathers! Do you even find the idea of provocation appealing at these days?

I subscribed to John Waters’s idea about shock value: that shock for shock’s sake is valid, that provocation for its own sake is perfectly legitimate in terms of artistic expression. The whole point of humour has been about saying things tha are provocative or offensive. So, people kind of miss the point of humor now; that the fact that you’re shocked is itself part of the appeal of humor.

In terms of writing, I think you just have to make your art as truthfully as you can and face the consequences. I’m personally not that big of a target, because I’m still more of an underground filmmaker, and also because of my body of work, I think people tend to think, “Oh, he’s at it again!”

Right, you still hold your status as “enfant terrible“?

It’s “ageing” enfant terrible, thank you.

In the case of someone like John Waters, his work is rooted in the art of bad taste. I was recently reminded of the scene from Polyester where Divine’s daughter declares, “I’m getting an abortion and I can’t wait!” That film came out in 1981, but considering the draconian state of American politics with the Texas abortion ban, doesn’t that disruptive humour feel more powerful and necessary now more than ever?

Absolutely, it is! Its scandalous that John Waters doesn’t get more recognition, but it’s good, in a way, because it’s exactly the way he would want it. He really is an intelligent and political filmmaker on the same level as Pasolini or Fassbinder. I believe Multiple Maniacs is equally as great a film as Pasolini’s Gospel According to St. Matthew.

He’s so subversive in a profoundly politically incorrect way, but it’s incredibly satisfying. It’s so brilliant when Edith Massey gives her speech about “the world of heterosexuals being a sick and boring life.” I tried to do that with The Misandrists, wherein the women are castrating, lesbian separatist terrorists, and, and, you know, you’re not supposed to think of feminists as man-haters, or even consider that there could be a vicarious thrill about the thought of castrating a man.

Yet, exploitation film is all about deep-digging into those naughty fantasies that you have that could be violent or sexually violent.

Well, Divine gets raped by a man-sized lobster in a Kafkaesque sex scene. How would you even begin to put a trigger warning on that?

It’s brilliant because he kind of transposes the anxiety and societal conversation around rape onto a kind of risible sci-fi exploitation trope. I mean, Mink Stole sticks a cross up Divine’s ass in an actual church! That was one of those scenes that really inspired me when I saw it for the first time back in the late ’70s.

It inspired me to not only challenge your audience’s boundaries, but to challenge my own as well. There have been so many times over the years as a filmmaker that I’ve had that feeling of, “Oh my god, have I gone too far? Have I actually offended myself?!”

The idea of cancellation seems so absurd to me, because I feel like I’ve cancelled myself so many times!

Speaking of shoving things up people’s asses, you approach your porn work with the same sort of academic intent as your other films. At what point does that risk becoming a boner killer for a presumably gay male porn-watching audience?

Well, I’m a recovering academic, but I’ve never completely recovered. So, my work sometimes can be academic and, you know, porn and academia are kind of strange bedfellows even though they shouldn’t be.

I just think it’s bizarre. It’s completely bizarre to me that more people don’t work in porn or try to break down the line between art and pornography. It baffles me. I mean, pornography has become very politically correct as well.

How so?

I can’t get into it, but trust me.

Is making porn hot for you or is it strictly professional?

Lately, I’ve been making more straight or bisexual sort of porn. I find it really interesting because, as much as I love and appreciate women and female sexuality, it’s not like when I make gay porn, which turns me on sexually.

It’s different. It’s almost more academic for me, even though I appreciate females sexually more on an aesthetic level. It’s a slightly different exercise.

It’s not academic exactly, but there’s a certain distance that makes me look at porn through a kind of filter, but I’ve always been that way about porn — I’m “The Reluctant Pornographer”!

I know you’re a big fan of Jerry Lewis, and your early films feature a slapstick type of humor seemingly inspired by his work. Do you ever feel that certain elements of your own work get lost to the more sensational aspects?

Well, it’s also camp, which is dismissed automatically. It’s not taken seriously. That’s why John Waters hasn’t been taken seriously by the arbiters of what is profound and great cinema, because they don’t understand how profound camp is as a concept and how deeply politically queer it is. So, it’s the same thing. I don’t think people really take me that seriously.

This young woman from Australia wrote a whole PhD dissertation on my work, which was about why my films are not discussed or taken more seriously in academic circles, for example, and why they resist co-option by academia and the mainstream.

She argues that it’s built right into the films, that it’s the opposite of being critic-proof — where certain filmmakers now can be critic-proof, regardless of how shitty their movie is, they have this canon around them that leaves them beyond critique.

Do you think you’d still be making movies if you were absorbed into mainstream culture, if that had been an element of your career?

I don’t think I’m absorbable, because I’m a freak. That non-conformity is built into me at this point. Resistance is my main motivating drive, you know?

Well, Vive la Resistance!

Vive la Resistance!

— Q&A by Kevin Hegge (@theekevinhegge)

Every time I read one of your posts, I come away with something new and interesting to think about. Thanks for consistently putting out such great content!

This was so beautifully written! Congrats.