What do you ask a “guitar god”? This was my first thought when I was recently asked to interview Johnny Marr.

What do you ask a “guitar god”? This was my first thought when I was recently asked to interview Johnny Marr.

“Johnny is literally the best, and he doesn’t mind talking about his time in The Smiths, or his relationship with Morrissey, but please try not to dwell on it,” warned Marr’s publicist in advance of our chat.

Marr’s early days as the guitarist and songwriter in the seminal, foppish (read: gayish) ’80s indie band The Smiths, and the subsequent fall-out with frontman Morrissey nearly eclipsed his career, and I vowed not be the type to broach the subject.

Despite the undeniable impact of being one half of one of the greatest songwriting partnerships of all time, Marr’s career following his time in The Smiths has been far from dismissible. Before endeavouring an official solo career in the early 2000s with his band The Healers, and a brief stint as a member of The Pretenders, Marr was involved with projects like the indie-dance super-duo Electronic with New Order’s Bernard Sumner. His covetable versatility as a musician led to pop-leaning collaborations with the likes of Pet Shop Boys, Talking Heads and The The.

A longstanding working relationship with the legendary film composer Hans Zimmer lead to what might be Marr’s most unexpected partnership yet, a collaboration with Gen-Z poster girl Billie Eilish. Marr worked closely with Zimmer on the score to 2021’s No Time To Die, which included Eilish’s theme song to the film.

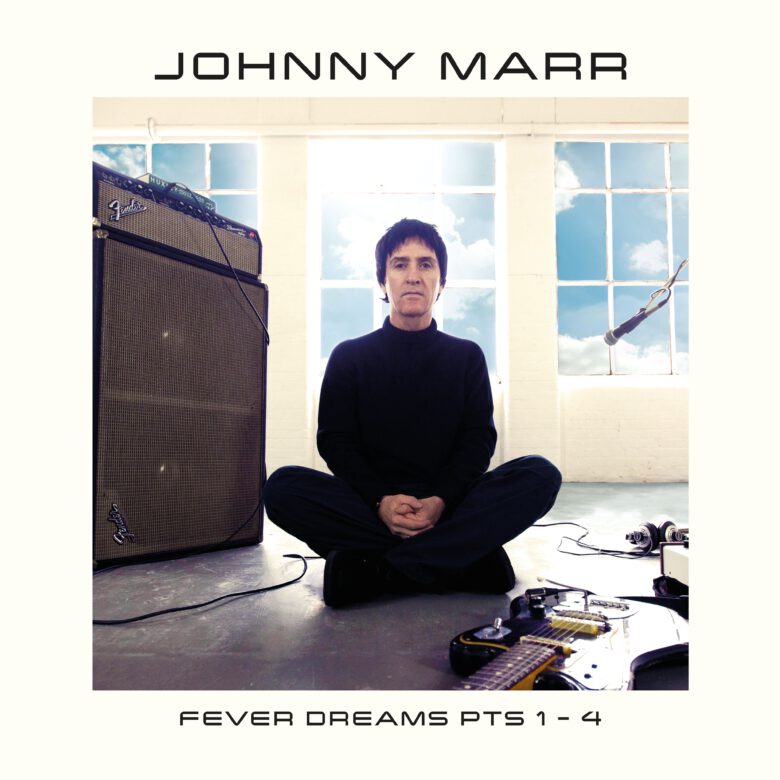

Marr’s official solo third album, Fever Dreams Part 1–4 (pre-order the album here), is already garnering critical praise in advance of its February release. The conceptually forward record has been released in four parts—3 EPs culminating in a full-length record, and finds Marr leaning into newfound territory as a songwriter.

Marr’s official solo third album, Fever Dreams Part 1–4 (pre-order the album here), is already garnering critical praise in advance of its February release. The conceptually forward record has been released in four parts—3 EPs culminating in a full-length record, and finds Marr leaning into newfound territory as a songwriter.

I was excited to speak with him about the record, and seconds before an affable, and candid Marr joined me on video chat from his studio in London, I realized that in the top corner of my frame was a limited edition box set of The Smiths complete biography—a rather deep collector cut if I do say so myself—and it seemed my intentions to stick to paths less-Smithsy were defeated before we even got out of the gate.

But as his publicist suggested, Johnny remained chatty and bright on the subject and dug right into some juicy behind the scenes details on the album’s art work. We managed to move swiftly beyond the past and talk about the lofty intentions for his new record and some highlights from his storied and thriving career.

Read the full Q&A with Johnny Marr after the jump!

�

KH: Well, that’s embarrassing [getting caught with The Smiths box set in the background].

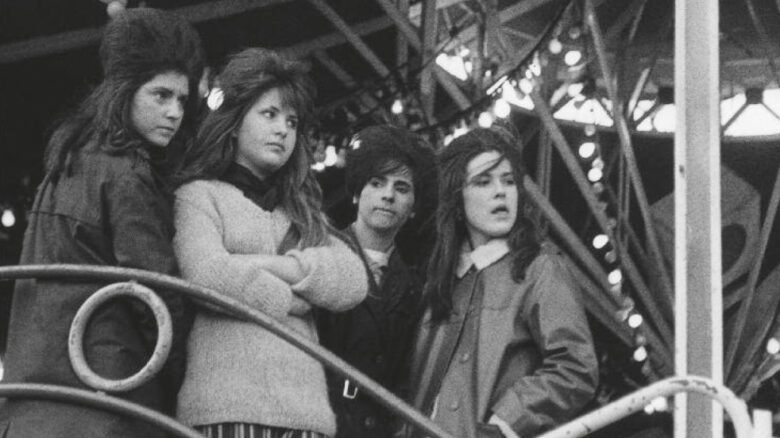

JM: Thats my favorite ever Smiths image, that. I was so pleased when that ended up as the cover of the box set. Do you know the story of that picture? It was on the back of the album The World Won’t Listen, but why it’s so clever—and I can’t take any credit for this myself—but if you look at that picture, the one on the left is Mike Joyce, and then next to her is Andy Rourke, then it’s me, and then Morrissey.

If you pull out a picture of the band and compare them, it’s uncanny!

Didn’t you handle all the of the remastering and release of that massive undertaking [the Complete collection]?

Yeah. Yeah. I was trying to get that together for about ten years! It’s a long story…

Speaking of massive undertakings, your new album is quite immense. Can you talk about your decision to break it down into four parts?

Well, seriously, it was born out of an artistic imperative. The title Fever Dreams Parts 1–4 came first, and then I had to work out what these Parts 1–4 actually meant. That’s one of the great things about making art, creatively it provided me with a kind of puzzle, where I had the answer, then had to work backwards.

What happens with me with ideas is I kind of wear them, and I just couldn’t shake this one off. I’ve been doing this long enough now to know that not all ideas would stick, but with this one I just knew what I had to do. Fever Dreams was a good title, but I knew It had to be Fever Dreams Parts 1-4.

I’d never made a double album before with all the bands I’ve been involved with, and I’d never done a record that had different parts to it.

How did you land on four? Why not ten or whatever?

Yeah I’m not sure, but it gave me a framework to work with, and so in the writing process I figured it would be cool to put out a few EPs, and then have the fourth part be the whole album.

I had these four whiteboards up in the studio and I’d have a couple of songs. I knew that I wanted the first song to be an electro banger—this all sounds like it was planned to perfection, but it just kind of worked out this way.

The electro-banger ended up being “Spirit, Power, Soul,” but then I would pull out an unfinished song, and think it would be good as part of the second release, or that one doesn’t fit the first one and should come later on and so on.

So the concept gave me a sort of artistic premise to follow and a structure that would otherwise not have happened.

It sounds like a similar process to writing a play or a a film script, in terms of “movement.” For songs that were written for this record, did you start writing them to fit into a larger thematic narrative, with a beginning, middle, and end?

Well, with every album solo I’ve done, I’ve always got to the end of it and had this feeling that something was missing, that there was something more I had do to. I needed to do something less planned out and frankly, emotional.

When I started writing the solo songs, to be honest, I was really put off, thinking everybody’s singing about themselves, everybody’s singing about their inner-world, or singing about adversity. The singers I like— Siouxsie Sioux, Howard Devoto and Pete Shelly (of 70’s pop punk pioneering band The Buzzcocks), or David Byrne of The Talking Heads—they don’t do that. They don’t vomit up their internal feelings.

So I made it a little bit of a policy when I started doing my own stuff to try and avoid singing about my own feelings. Not that there’s anything wrong with the other songs, but with the first and second records, I always felt I had to add something sincere.

There comes a point where the record needs something and it’s usually that you need to connect and sing something personal.

When I started writing Fever Dreams, I heard this voice saying to me that I need to do that a lot more.

In the past, I’ve used devices like psychic geography—I like singing about buildings and I do that to circumvent earnestness. On this one, I considered the idea of singing about my feelings more, and realized it would make me a better writer. It goes against my usual inclination, to go digging deep, but the challenge was finding good, poetic ways of singing about not only your own feelings, but universal feelings.

Lyrics like:

“Yesterday is gone / Today I’m so on the run / How strange tomorrow will be / For you and for me / ‘Cause we got soul, don’tcha know? / Now put your faith up in the sky/ And see the blues in my eyes.” on “Spirit, Power and Soul.”

I wouldn’t have really written lines like that before. I would’ve maybe been a bit too self-conscious.

I also didn’t have any kind of indie rock or punk rock kind of hang up about it being a double album, I got quite excited about the opportunity to be a bit more expansive and epic, and not so tightly edited as usual.

The record does feel very thematically cohesive, despite its four chapters, and the fact that it is so sprawling. The second song, “Receiver” reminded me of the opening of Bowie’s “Diamond Dogs, Future Legend.” It feels like you’re about to set in on a journey of sorts in that very cinematic way. Did your long-standing collaboration with Hans Zimmer, and the fact that you were working on the James Bond movie with him at the time play into that at all?

I actually did write that song in the down time while working on the Bond movie. I think as far back as working with Hans on (Christopher Nolan’s 2010 film) Inception gave me the license, or the confidence to do the more expansive thing. There’s a song on the album Call The Comet called “Walking To The Sea,” which is deliberately cinematic. My plan was to get Hans on the track, but we’re both workaholics and we never got round to it.

As I started writing this new record, the Bond movie started to happen, so that interrupted me for a few months. There’s a lot of downtime on movies so eventually I was back to living a fairly nocturnal life again, walking around Soho and writing stuff that sounds very nocturnal and kind of erotic.

I’d be going to clubs, and with “Receiver” in particular, it was meant to sound like something you would hear at 3:30 AM and the kind of signals we put out to each-other at that time in the morning. It’s got a bit of a Berlin feeling to it.

In terms of instrumentation, you play a lot of stuff other than guitar, right?

I play everything except the drums. Yeah.

Do you feel like your reputation as a “guitar god” diminishes peoples understanding of the scope of your artistry?

You know what, it’s funny because I’ve been doing it so long that over the years I’ve been asked the question, “What would you have rather have on your headstone, being a songwriter or being a guitar player?”

To honor the little boy I was, growing up and listening to bands, I’ve always said Guitar Player. I have this sort of simplistic feeling of carrying the torch of nobility with the art guitar playing. It’s interesting that you ask this now, because 20 years ago, whoever was producing a record would be part of the picture.

To get noticed as a producer these days you have to produce a big pop track like Adele or something. Otherwise, no one really cares who produces a record anymore because we all know someone who can produce a pretty good track these days.

It’s just a part of technology being a part of the culture now, whereas I produced The Smiths records, the ones that John Porter didn’t produce. Everyone now knows I produced them, aided and abetted very well by Steven Street. We were all young, and that’s a whole other story, but to give the united front—and I was more than happy to do that—I gave myself and Morrissey the credit. But in actuality, I produced the records.

So the first one I did when I was only eighteen or nineteen years old. I produce all my records with and also work in studio with this guy James Doviak, who is an absolute Jedi with Protools and all that.

When I come to the band with my demos, they’re all there. The other drums are produced, I play the bass and I play the keys and I arrange all the strings and I do the backing vocals and all of that stuff, like a lot of musicians do. But because I’m known for being a guitar player, that’s the deal I make, and frankly, I’m very proud to be known as a guitar hero because, coming out of the time that I come out of, I’m just glad that hasn’t died!

I wonder if your commitment to the humility is rooted in a sort of working class, Mancunian upbringing? Is it similar to a punk sensibility, rejecting all the grandiosity of the pop construct?

I don’t have any hang-ups about it, but yeah, I’m sure. I think of myself as a working musician. I think it’s a healthy way of getting the job done. I can speak on an almost mystical level about what I think it means to be an artist and musician, both in culture and to me personally, and I think thats valid, but it’s useful for me to maintain that position of being a working musician, because it makes me get the job done without being too crazy.

You said in a press release that many of these songs are the results of ideas you’ve been collecting for decades now. Are there any songs that landed on this record that you can pinpoint the source of the song and why it ended up taking shape here?

You said in a press release that many of these songs are the results of ideas you’ve been collecting for decades now. Are there any songs that landed on this record that you can pinpoint the source of the song and why it ended up taking shape here?

I appreciate you asking that because yeah, there are. I’ll just preempt it by saying that when I was a kid, I learned to do what I do from studying records. My learning of chords and keys was playing along with 45s, and they would’ve been records by Sparks, David Bowie, T. Rex [read the OMG.BLOG Q&A with Gloria Jones here], and so on. I was a teeny bopper, but at the time, the music that was made for teeny boppers was made by these really amazing people. So I got really lucky there. I would think of these songs as a total wonder.

Now, when I write a bit of a song where I know I’ve got something good, I’m lucky enough to have people in Tokyo, people in Toronto, wherever—around the world—come up to me after a show backstage or online and say, “That bit that you did, I love that bit!” It’s very gratifying.

I now know that when I’m lucky enough to find those parts on records, someone is gonna feel it too.

You’ve frequently collaborated with bands that followed in your footsteps. How often do you find people seek you out for projects based on your icon status or cult of personality, versus the skills and sounds unique to your output as a musician? Do you still find yourself ending up The Smiths guy?

I’ve been sought out a couple of times, once with Modest Mouse, and it worked out great. Best time of my life, man. We made a great record and we played some amazing shows. But that whole trophy thing, if it was to happen, that’s only gonna last two hours because I’ll see through that within seconds and then get out of there.

I feel like when you hear certain music you can kind of anticipate whether you’re going to like that person through their music or not. When I heard Hans Zimmer’s music for The Thin Red Line, I kind of sensed from the emotion in it that he was a great guy and in the end he turned out to be a great guy.

The music industry is a small world. People know if you’re a dick, but I think I’ve got a reputation for being a pretty nice fellow. I can bite when I need to though; I’m not that fucking nice. I don’t put myself in a position where I’m just kind of used as a trophy or any of that.

I’m pretty sure that nearly every relationship, apart from the very obvious one (Morrissey), that I’ve had working in music has really lasted, and I’m really tight with those people.

There’s a chicken and egg element to your career. You are drawn to these collaborations with kind of moody, verbose front men…

…and women! Yes! A lot of these people you’ve played with would’ve grown up being moody and listening to your records, so where does that start and end?

Yes! A lot of these people you’ve played with would’ve grown up being moody and listening to your records, so where does that start and end?

I think it takes one to know one. I think I get asked by people like David Byrne or, Chrissy Hynde, or Isaac Brock or even Pet Shop Boys—they assume that I’m gonna bring something that isn’t straight, you know?

All these people I mentioned like getting in the ring and they like having hit records, but all of us—Smith’s included—we’re in the business of slugging it out in the mainstream. Gate-crashing the mainstream. Modest Mouse were number one in the album charts, you know, and I was so proud to be part of that guitar music, that really wasn’t making it onto charts at that time.

The Smiths got in the charts. I played on more Pet Shop Boys records than any other musician, which makes me very proud. I had a big hit with Talking Heads. I don’t like the mainstream man, but I but I don’t wanna be in the gutter either.

The thing I love about pop culture is when figures like Bowie and Neil Tennant and The Smiths and Mark Bolan, and now Billie Eilish—these people with interesting ideas gate-crash the mainstream and people’s parents have to deal with it.

When The Smiths appeared on Top of the Pops we knew what impression we were making, and we had the guts to do it. So sure, I like having hits, but I’ve been very lucky, and I think the people who are attracted to me and have been in the mainstream are still cool.

I’ve turned down a lot of people because it just didn’t fit, or because I just don’t wanna be involved with something that’s shit.

— Q&A by Kevin Hegge (@theekevinhegge)

Johnny Marr’s new double album Fever Dreams Pts 1–4 is out February 25th via BMG and available Pre-order here.

Be the first to comment on "OMG, a Q&A with Johnny Marr"