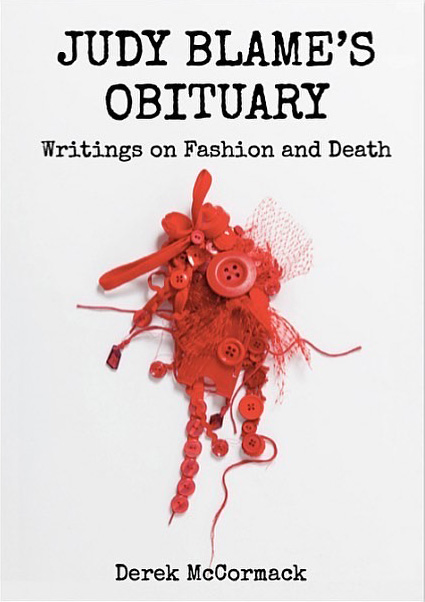

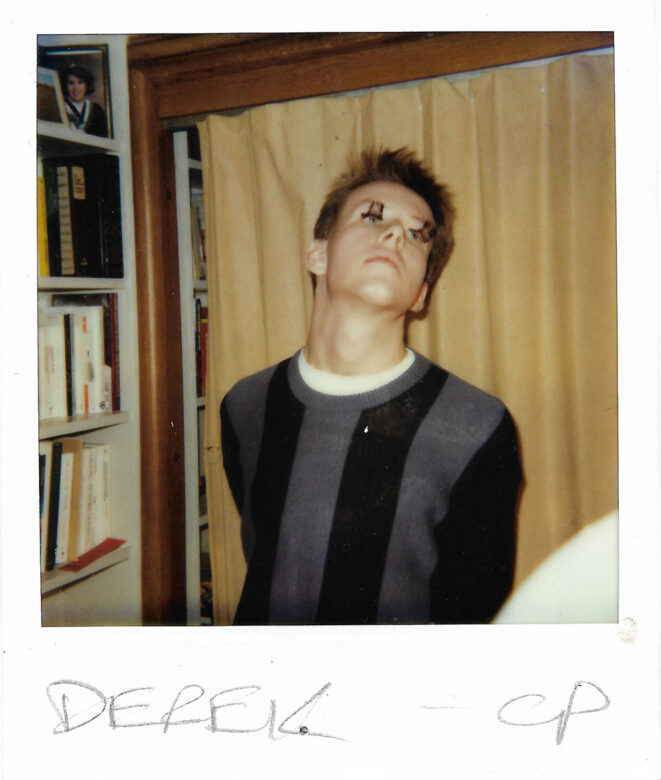

The first lines of the Author’s Note in Derek McCormack’s new book Judy Blame’s Obituary: Writings on Fashion and Death state simply:

“Fagginness is what I write about. I focus on things that fags love: fashion and death. Think about it: all fags wear fashions—I’m wearing some! And all fags love death—I’m dying!”

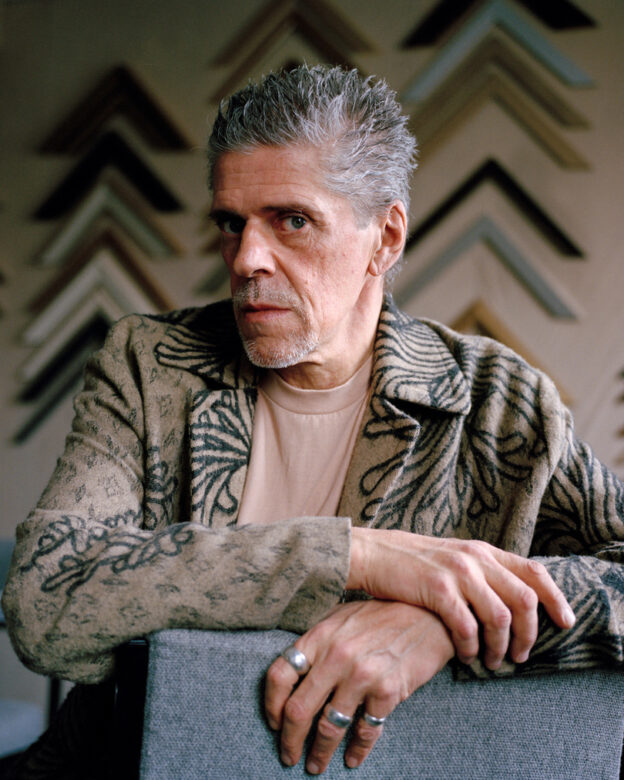

In 2012, McCormack was diagnosed with cancer, and given five years to live. Ten years later, he has released a collection of essays, spanning his career and focusing of his work in fashion, and ruminations on death—two subjects which seamlessly intermingle in McCormack’s world.

Published by Pilot Press, a young, independent publisher based in London, UK, Judy Blame’s Obituary marks McCormack’s thirteenth published book since his first in 1996. Its title refers back to an obituary McCormack wrote—originally appearing in Artforum—for the legendary UK-based designer, stylist and fashion icon Judy Blame. Blame passed away tragically in 2018, leaving an immense cavity in the world of British fashion, after serving as a source of vital inspiration to the author and creative people internationally.

McCormack credits the torment of growing up as a young homosexual in a rural Northern Ontario town as the driving force behind his work. The disgust directed at him by the general public is a two-way street. In his work, he documents the palpable disdain directed towards him by normals, jocks and filthy heterosexuals—a disdain he continues to gleefully savour in his often confrontational, yet consistently humorous work.

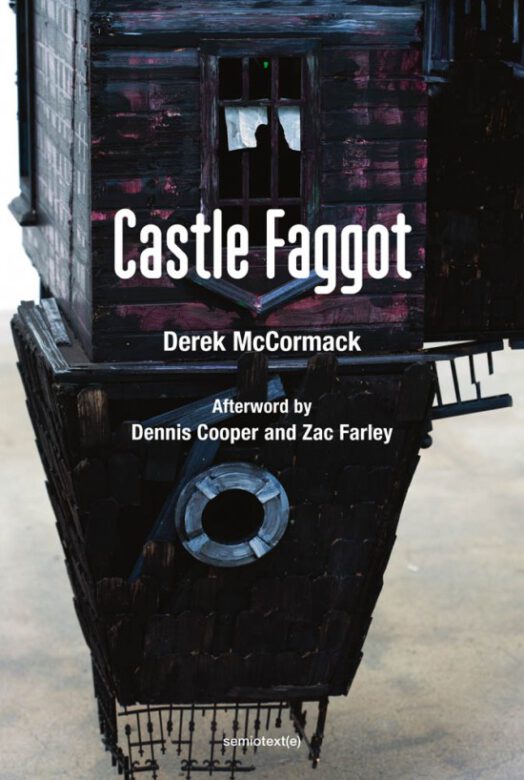

The new book steps away format-wise from his novels of late, such as 2015’s The Well Dressed Wound, and most recently, the concept-heavy, scatological sick-fest that is 2020’s Castle Faggot, both via avant-academic American publisher Semiotext(e).

The new book steps away format-wise from his novels of late, such as 2015’s The Well Dressed Wound, and most recently, the concept-heavy, scatological sick-fest that is 2020’s Castle Faggot, both via avant-academic American publisher Semiotext(e).

McCormack’s books unfold like the mirror mazes he describes encountering on the fairgrounds of his youth: warped, horrific and hilarious.

His world is populated by glamorous ghouls, fanged fashionistas, and of course, haunted hillbillies. In this world, Dracula, a life-long love and frequent character in McCormack’s work, somehow comfortably inhabits the same space as the ghost of country legend Hank Williams.

McCormack’s preoccupation with death may come off as macabre, which of course it is, but his delivery of all things deadly is a type of sinister slapstick, filled with wordplay and vaudevillian folly. He’s the goth haunting the halls of the old school.

Judy Blame’s Obituary serves as a totem to the writer’s history not only in regards to his work, but forms an inadvertent autobiographical portrait of the author himself.

We sat down to chat with McCormack about how the book came together, and how it feels to unexpectedly and simultaneously mourn and celebrate his work up until now.

Read the full Q&A after the jump!

�

How did a small town homosexual like yourself develop such in-depth obsessions with fashion houses like Comme des Garçons at such a young age?

Thankfully, my parents subscribed to a major newspaper called the Globe and Mail. A man named David Livingston was the style editor at the time, which was vital for me. At that time, he went to all the shows, knew all the designers, took Polaroids, and was a great writer. So I would keep the Thursday Style section under my bed in a big box.

A big part of that was learning all the names in fashion, but [the Globe] would also note where the clothes were sold, so if my family ever came into the city, 11-year-old me would take the subway to find the address and wander into it, scared shitless.

So many concurrent childhood obsessions are revealed in this book. You’re obsessed with Halloween, but also country music. You’re obsessed with feces (we will get to that later, readers), and also the word “faggot.” It’s hard to know where to start to unravelling all of it, but this collection does manage to make all of those aspects cohesive. Can you describe how all of these things became part of one picture for you? How did you make the Dracula aspects marry Hank Williams?

I have to think it’s like a tribute to how limited my mind is. No matter what I’m exposed to or what I’m assigned to do, or how old I get, I keep going back to the same things.

I guess one of the wisest things I’ve done is to not to feel bad about that, to just encourage it, to mine it, and to keep mining it, even when it seems like a dead end. I think for me there’s a polarity there, of being a rural kid—I dreamed of being sophisticated and cosmopolitan—but when I got to the city, I had a deep home sickness for the rural.

You ended up embracing your ruralness?

Yeah! I grew up on country music. I loathed it until I moved to Toronto, but then I would go home and say, “Do you still have those Hank Williams 78s?”, which shocked my parents, having made them go to Bowie concerts and Siouxsie Sioux concerts for so many years.

It was being here that made me love there. And being there that made me love here, which I find also happens in a lot of my work.

When I’m in the fashion world, I think of myself as literary but when I’m in the literary world, I think, “Oh, I love art.” When I’m in the art world, I think I actually love fashion. I don’t always feel comfortable where I am, but I have this continuing fantasy that I am home somewhere, and the fantasy is what I keep feeding, even though I don’t ever arrive at that place.

I think that’s what happened with the country music and vampires and fashion. I have these loves, I don’t ever swear them off. They might get tucked under the bed for a while or shoved in the box in the closet, but there’s always a way to loop back them.

In terms of writing, especially my fiction, I do really consciously work at that. I do think about how I can find a framework within which I can contain them all. I work really hard to construct a scenario that can hold the things I love together, even for like an hour, and they don’t really go together. I think they might vanish in a puff of smoke after you’ve done reading them, but for the hours it takes you to read them they manage to coexist.

The book seems intentional about this loop of obsessions. Where some publications would edit out repeated themes, this collection will feature one piece centered around, say, Margiela, and the following piece will blatantly continue that same theme. Did you address that when compiling these essays?

It shows you that, in a way, I was a terrible fashion journalist. No matter what was given to me, I would find a way to work in the things I really wanted to talk about, say Schiaparelli and Margiela. It didn’t matter to me.

So, in a way, I was just one note, but in another way I loved it so deeply that I think that’s why they kept coming back to me. I love the history of “stuff,” which fortunately they indulged me in at the paper I worked at.

I really cared about, “Who made the buttons for that? Who did the sequins, or what happened to that kind of stitching machine?” But when I put together the book, I thought maybe it was weird that I had double chapters about Margiela or three pieces about my friend, the artist David Altmejd.

Some of these themes, such as the work of David Altmejd—or Dracula—span many years in your work. It’s normal to champion someone’s work, but here it feels almost like you’re operating as a biographer of these subjects. Is that how you perceive your work?

I hadn’t thought about how I did meet David through my work, and we did form a friendship. I guess I do have these relationships with Margiela, with Dracula and with Hank Williams, and they all continuously deepen, too. It’s as if no one told me, “Derek, you actually have nothing to do with these people. They’re not your friends, you have no relationship.”

I think what happens in this book is a reflection of the fantasy of being a small town kid, which is that, though I was connected to nothing in the broader world, I really diluted myself into thinking that I was.

I think that delusion never ended for me. Like, I think that it maybe was the best part of my personality and I just kept cultivating it. When I finally got to Toronto and was confronted with actual cool scenes and cool people, I liked it, but it mattered less to me than the fantastic ones in my brain.

The other answer is just that… Well, what is the answer? What kind of person is so obsessive about the same things for decades?

Did your work in fashion not flag the fact that you were meant to be looking forward and translating newness to the general public?

I think that when I became a writer, I realized that I would do anything, and anything that gave me a spark to write became the most valuable thing. So, I never actually questioned my obsessions or how longstanding they were, how silly they are, or how much they cost me if at some point they helped me write a book.

I guess I’m kind of shameless about that. I’m chasing a feeling in a book, or I want to create an effect and I’m just merciless. I’m mercenary about getting that.

There are pieces in the book that are just so detailed, down to describing where and how sequins and buttons are constructed, to the nature of the thread. I mean, fashion is one thing, but you go into detail about the origin story of the Whoopee Cushion for instance. You completely eviscerate the common idea of Christmas and its origins. One has to wonder: Do you just know this stuff or are you using these articles to further your research about a topic?

There are pieces in the book that are just so detailed, down to describing where and how sequins and buttons are constructed, to the nature of the thread. I mean, fashion is one thing, but you go into detail about the origin story of the Whoopee Cushion for instance. You completely eviscerate the common idea of Christmas and its origins. One has to wonder: Do you just know this stuff or are you using these articles to further your research about a topic?

Oh, that’s a great question. I think, in a way, in all those articles I’m testing out ideas for novels. Like, I think that they are test runs for things I want to write fictionally, and an excuse to research things that goes in my book. It’s a sounding board for sure.

I’ve had this one document for like twenty years, collecting lines I love, images I love, and facts I love. The truth is that I can’t remember where any of those lines came from or what I made up and what’s fact or fiction! So that’s another thing that’s in my favor as a journalist. I’m willing to say things that I can’t fact check, no one can fact check.

I love making declarations about things and people will say, “Well, how do you know the best Gorilla suits were made in Hungary?”

And I’d say, “Well, I don’t anymore. I might have made that up and I might have read it. It doesn’t matter to me anymore because it’s true now that I’ve written it.”

I found that when I write for magazines with fact checkers, it becomes a problem, but something I actually love about my fiction is that I put real facts in there that seem completely preposterous, and in my nonfiction, I put fictional lines that seem preposterous—it’s all the same to me. It’s all my fantasy in my head.

So, I don’t think I’m an award-winning journalist, but I keep it interesting for myself. I make big declarations about things that basically no one can research.

There’s no other way than to just just ask: When did you become so cuckoo for caca? Feces is a consistent theme and image in your work, from talking about fragrances with fecal notes, to the full blown shitstorm that is Castle Faggot. Is that rooted in your urge to disgust people that you describe feeling as a child in the intro to your book? Did your use of shit as a device evolve from a gross-out tactic into a more conceptual tool for you?

I guess the origin would be being a faggot, and being thrilled, as a teenager reading Genet, at the connection between butt-fucking and shit. It was a way as a young fag to say, “You think I’m disgusting? Well, actually I’m even more disgusting than that! And we all are.”

I would say it transformed when I got cancer and was fitted for an ostomy bag, which I did not end up getting. I survived these surgeries, the last of which was eighteen hours long. I was in ICU for weeks and they said, “You’re alive, go live your life!”, but what I didn’t realize was that I would have no bowel control for a year. There was no living my life. I had to live next to a bathroom. I live in a bachelor apartment and ideally I would have five bathrooms in here, because, since cancer, it has become like the unruly god that I have no choice but to answer to.

People always hated my body, because I’m a fag, and my body really hates me, is what I learned. It always has, but the cancer kicked it up another notch. I became just an agent to carrying and ridding myself of shit. I still am.

So, my relationship with the body changed because I always hinted at shit as a device, and it was quite campy, but with The Well Dressed Wound and Castle Faggot, I thought, this is actually the center of my life. This is like the thing that is controlling my life, so how do I write about it?

It’s still ridiculous and campy, but everything is getting reversed here, where the body is at the lowest part of my life. There’s my body, and then above it there’s cancer and there’s shit, and I’m just getting knocked around it all like a rag doll.

I try and keep it funny, but for sure, my relationship with life and death, which is mediated by shitting, has changed. I didn’t know if I was going to live. The weird thing with my cancer is that it’s deadly serious for me, but also the most laughable thing in the world—the level of grossness that I have to deal with and that people that have had my cancer have to deal with—because it’s so normal for me, but I realize it’s also super-charged for other people to hear.

Your most recent shit-centric novel, was Castle Faggot. I wonder what your personal relationship is with the continued use of that word, wherein societally speaking its become pretty unpalatable. Is the joy of it exclusively in its disruptive quality?

I was always called a faggot. I was called a faggot by my teachers, family members, peers. I was called a faggot by my friends. I have never heard a more delicious word, in that it contains so much loathing and so much violence. I remember being shaken by being called that, but I also remember that moment where I realized how liberating it was that I really was that vile thing they were describing.

I guess it has become more prevalent in my work, because I do remember a time as a writer when people started calling me a “queer writer” and I hated it. In their minds, because I was a gay writer they thought I was a queer writer, but if we get to choose our descriptors, I choose faggot. Don’t call me queer. It’s weird because people call you queer, but they never ask if you mind being called that or if thats how you want to be described.

“Faggot” has become more prevalent for me because one, it’s mine, and two, I find that it disgusts queer people sometimes. That disruptive pleasure is not only applied to straight people, It’s applied to queer people as well. So if that’s a disruptive pleasure, I’m gonna indulge myself in that, for sure.

If you had a publisher other than the radical-leaning Semiotext(e), they might have made you change the title to Castle Queens or something!

If you had a publisher other than the radical-leaning Semiotext(e), they might have made you change the title to Castle Queens or something!

Well, they should have, because I was so naive; I had no idea how people would not engage with a book with that title. They wouldn’t review it. They wouldn’t say it was even coming out.

I had people write reviews and the reviews were nixed because no one would even publish reviews of a book with that title.

I think that deliciousness of these ideas is very central to your work. It’s kind of magical that you’ve been able to exist in this totally free vocabulary that you’ve created. It reminds me of a time when things were still illicit, and by engaging with your work, the reader feels like they themselves are engaging in something dangerous. It’s actually very joyful to experience. Have you ever imagined a world where your work is more widely recognized, and the irony of the detriment that might actually be to your career?

I do wish more people would read my work because I feel the readers I have are amazing, but I’ve never made any money or gotten a grant or anything like that. I’ve gotten to meet people I really adored from a distance and people I didn’t know I adored, but my readers are people that get a kick out of it, or find it funny, and we’re just in sync.

Growing up, I did get a charge from the illicitness of gayness and the power it had to discuss. What I learned was that parts of it will always be illicit. Like, there’s mainstream gay culture and there’s [Canada’s public broadcaster] CBC-type queer culture, but there’s still us. There are still perverts.

I thankfully realized that the perverts are still in the shadows. We kind of like it there. We’re jacking off.

You describe objects in extreme fetishistic detail. Did you ever consider including images of the objects you discuss in your work, or did you want the reader’s vision to be contained to what you tell them?

That’s a good question. I think it’s really laziness. Like, I could not handle the thought of brokering reproduction fees and image fees and tracing stuff back. When these pieces would come out in various newspaper and magazines, there would be people whose job it was to source these beautiful images for me. I never had to do that work.

That said, I played with the idea a bit in Castle Faggot, where there are these boxes where there should be photographs, but I deliberately put no images there.

How do you marry your work as an archivist by nature, and your work as a fashion journalist, with your tendency towards fantasy?

Fashion is interesting, because it’s always already dead. In a way, it’s like what being a fag was to me as a kid: you’re already dead. When something feels right or important in fashion, it’s usually just a mass delusion and that can shatter easily and it can be forgotten overnight.

I love that about fashion. I love that it can feel really solid, really important and really about artisanal work, but the actual magic of it is so elusive. And if you look too long, it’s gone.

The dead world in your work feels so liberated. It’s like a playground populated by glamorous, playful entities.

I love that. I love that it could be a liberating force—in the same way shit could!

How did your relationship to all things macabre and mortal change with your cancer diagnosis?

A friend said to me that it was the greatest thing that ever happened to me. I had been so morose and such a hypochondriac and so death-fixated, but then I had to deal with it in a very real way twenty-four hours a day.

When I went in for what was to be my final treatment, part of the process is saying goodbye to your family, writing a will making sure someone has a key to your apartment. So, in a way, it was just the most calamitous and hilarious joke that had gotten played on me.

In a way it really made me. The sickness somehow took a sketch of me and made me like a full garment. It went to the runway.

The tone of your work never shifted into this ultra-positive, repentently gleeful thing that often happens once someone has brushed with death. Did you sway any of those urges?

Oh, fuck no! I still don’t know if I want to be alive! I mean, it’s like a mixed bag living with this. It’s like a blessing and a curse because you live in this impaired, traumatized state.

That said, it really freed the anger in my writing and it really freed the “fuck you” in my writing. Is it a high price to pay? Yes. But on the other hand, it’s almost worth it, because it sort of crystallized things.

I had always always played with tropes of horror in my work, but it gave me horror in my life. It was a gift of horror.

Does your experience with cancer heighten your relationship to other artists that have suffered it as well? Did it shape your relationship to someone like Judy Blame, who you are a big fan of, and who passed away in 2018?

I hadn’t associated his work in any way with sickness or death before. For me, it was all pure vitality, and when he died suddenly, it frightened me.

And then I thought about the cigarettes, and I thought about living in squats. I thought about the prices you pay to keep doing work.

The art of survival.

Yes! When they presented images of possible cover images, it never occurred to me that the one we landed on was a heart. It looked like a heart.

That kind of sinister view of his work never happened until I had to sit down and write about it. As I say in the book, I was writing about me. I was writing about getting diagnosed, being in the hospital, almost dying, almost having my liver fail—and these things happen to him.

It was like a terror to write about, because I was writing about me.

What does it mean for you to collect all these essays under the title Judy Blame’s Obituary?

I originally wrote the obituary for Artforum. It was only 800 words or something, but I had so many people say either it’s the best thing I ever wrote or it’s the only thing they like that I ever wrote.

I know this sounds childish to say, but I did always associate his work with life and creativity, and considered him a giant source of those things. When he died, it was so sudden, and I had admired him for so long that there was something in his story that became emblematic of just how terrible cancer is—how terrible illness is—how it creeps up, even on someone as seemingly unstoppable as he was.

Given the autobiographical nature of the collection, was it intentional that the book functioned as a sort of casket for your life leading up until now?

Everything I do after cancer is posthumous. I haven’t written fashion for a really long time and I’m questioning myself about that. I love fashion, but is this the end of writing about it? I don’t know how much time I have left, but I do know for sure that I don’t have the energy to do what I used to do, which is like research, write, obsess feverishly, and produce and produce and produce. So, in a way, it is marking a period that is over. It has to be over.

For the last three years, I’ve been making jewelry. I have like a hundred pieces of jewelry, and while I’m making it, I’m writing an essay as though it’s an exhibit catalog. I’ve always wanted my words to be like jewelry or like paragraphs to be broaches or lines to be sequins.

I’m finally writing something and illustrating it myself. So that seems like a logical step, but it’s only in the last couple of years where I thought, “Well, I’m not humiliated to do this or to tell people about it.”

You’re having your Mugler moment! You’re quitting fashion and going to join the circus! How do you feel now, after having written so fetishistically about fashion for so long, to have this book be out there with you yourself at the center of it?

I never thought about that, but I guess I did put myself at the center of it! I must have known it on some level, but I guess I’m surprised now that it’s out, how other people are noticing.

I thought maybe people would just get lost in the worlds I was describing within it, but people are actually noticing the kid from Peterborough underneath who’s writing it.

I guess it turns out that, for twenty years, I was writing articles that were basically about me! I’m just glad I wrote enough that was okay to make a whole book.

— Q&A by Kevin Hegge (@theekevinhegge)

Judy Blame’s Obituary is available online at Pilot Press and in good bookstores internationally.

Be the first to comment on "OMG, a Q&A with author Derek McCormack"