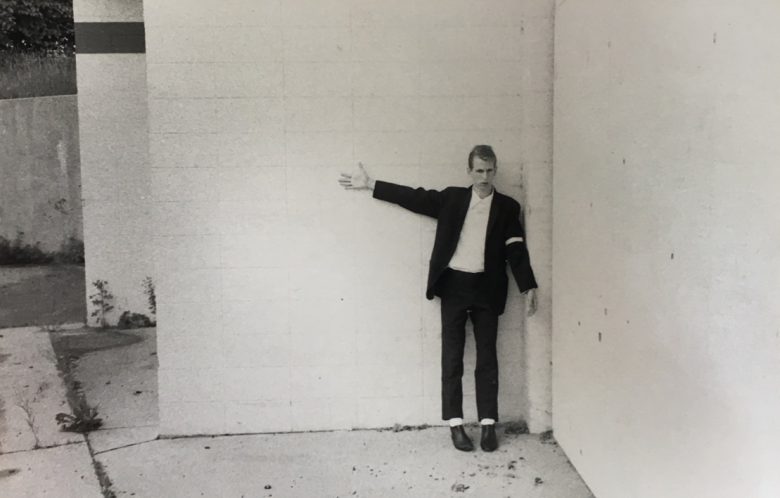

In its earliest incarnation, the North American punk scene was a type of social art movement, often populated by aimless kids from broken homes, fumbling through the night to mould the chaos of youth into some sort of meaningful experience.

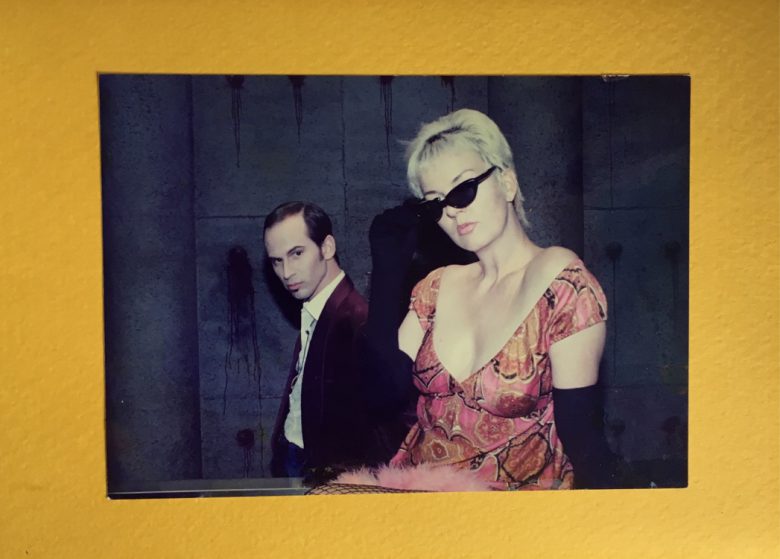

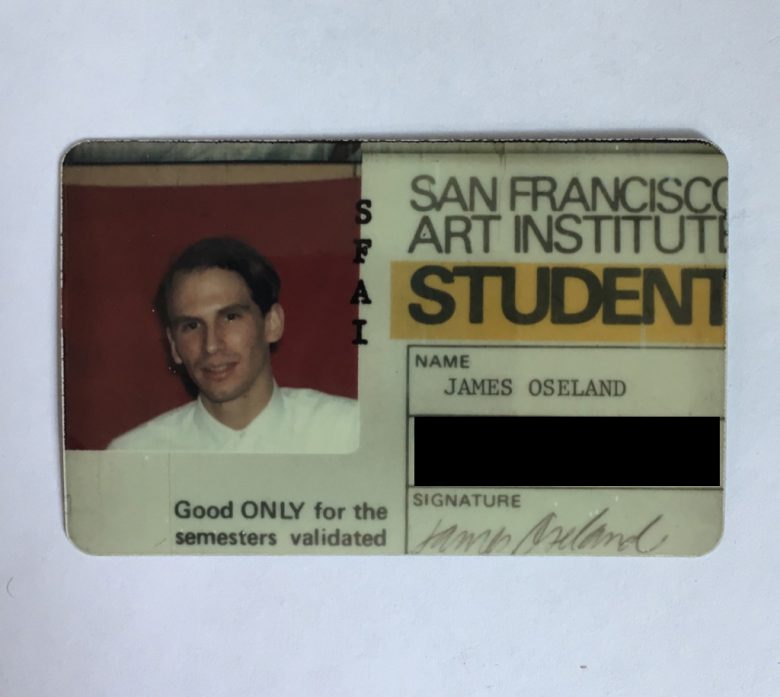

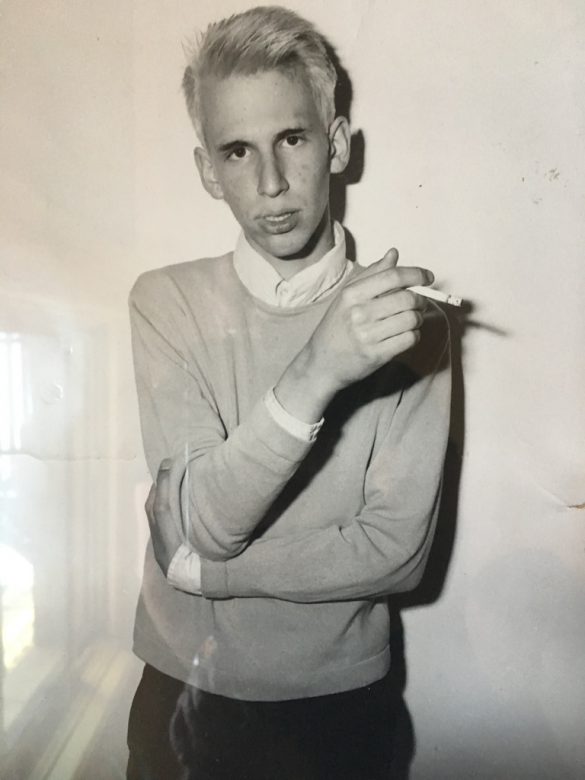

By the time James Oseland anointed himself “Jimmy Neurosis,” he was well acquainted with the seedy, yet somehow innocent underbelly of the San Francisco punk scene – which was itself, in 1977, only beginning to take shape.

In his book, which arrived last month as a paperback, Oseland describes the way the birth of punk helped him navigate survival in desperate times as a gay kid in a low income, single parent family before there was any template of how to do so.

Nowadays, Oseland is better known as an award-winning food writer and his five-season run as a judge on the Bravo show Top Chef Masters. We got the chance to chat with him about why, at this stage in his career, he decided to revisit these traumatic, yet formative years in the punk scene and how those experiences play out in his life now.

Read the full Q&A after the jump!

�

Your memoir Jimmy Neurosis describes three very formative years of your life — 1977 to 1980. Can you give us a breakdown of what the arrival of the punk movement looked like during that time?

I had no idea punk rock existed when I discovered it as a 15-year-old. Punk rock, as I knew it in its Northern California incarnation, was a local adaptation of something that had been in the water in New York for about a decade, but had coalesced in London in the mid-seventies. The Northern California version of punk was diverse—the scene was made up of everybody from teenagers to middle-aged people.

It was very gay, too, and multicultural. There were a lot of people in the scene who were ex-hippies. Punk rock in the late seventies was kind of the next logical chapter for many former Bay Area hippies. It was the next valid social and political movement.

When you were a kid did you recognize it as such?

Yes. The people in that first wave of punk rock in the U.S. came from diverse backgrounds, but we were bound together by a general sense that something wasn’t right in the broader culture. It was a sense of not belonging that brought us together.

We were outcasts, misfits. We were the people who questioned the structure of civilization as we saw it, and we found each other and figured out how to have a good time while the world crashed and burned around us. Or at least that’s how we experienced it.

You mentioned the birth of punk as having happened in England. Historically each region that manifested their own punk community had their own distinguishing traits. In their 2001 book We Got the Neutron Bomb: The Untold Story of L.A. Punk, Marc Spitz and Brendan Mullen describe the west coast scene as a very raw underbelly, as opposed to London’s very politically charged punk scene, or NYC’s arty conceptual community. What was your impression of how California differed from those other communities?

Well, I’m not yet familiar with that book, but that’s just part of the story as I know it. Between 1977 and 1980 there were two distinct versions of California punk rock—a Northern California one and a Southern California one.

The Northern California version had a more overtly political bent to it. For me, arguably the greatest Northern California punk rock anthem of that period was a fantastic song called Class War by The Dils. The Dils were originally a Southern California band, but they found their artistic home in Northern California.

The song is about the disgruntled individual’s place in the larger culture and for me it exemplifies the tone of Northern California’s punk rock scene.

How did that differ from what was going on in L.A.?

Well, I didn’t know L.A. as a teenage punk, but Northern and Southern California were very different places in that pre-Internet and social-media time period. Actually, it’s important to acknowledge the late-seventies as a completely pre-computer era—computers didn’t enter the consumer world until about eight to ten years later. We found out about punk shows through fliers and word of mouth.

But, back to your question: There was a lot of cross-breeding between the L.A. and San Francisco punk scenes. The biggest night of the year was when the band X came up from L.A. and played clubs in the Bay Area for the weekend. For me, X was the greatest punk band of that moment. They were fantastically focused and raw. They made music that sounded like I felt inside.

In the book, you describe some of your earliest experiences delving into the punk nightlife as being initially very intimidating. You even attended a Mutants party where someone died. The combination of seedy venues and strange creatures who were already initiated into the subculture known as punk might have scared other 15-year-olds off, but you continued your exploration of this underworld. Was that bravado a product of your naivete? Was it a recklessness rooted in the disruption of your family life? What do you credit for such fearlessness at that age?

Well, the odds were against me. I was a lonely, skinny gay kid with a thyroid condition who came from a just-broken family. We had no money, my mom and I—my dad wasn’t paying alimony, and my mom hadn’t worked in 25 years, so she became a part-time secretary. We were a wobbly version of our family that had just crash-landed in California. Plus, there was also the fact that I was mercilessly bullied in my new high school.

It was a difficult time for me. I was basically friendless, sexless, and about to go out of my mind, but as fate would have it, I was exposed to punk rock, which I immediately saw as a doorway. For me, going out at night wasn’t scary—it was thrilling. Sure, bad things — even terrible things — happened during that period. But I was stepping out into the world and I loved it.

Despite the relentless bullying you experienced, you seemed to maintain a sense of humour about it. There’s a very gruesome depiction of your being gay-bashed in the book, which must have been troubling to revisit, but other times a lot of the name calling comes off as almost comical, such as one incident when a driver by screams, “Weirdos suck cock!” Can you speak to these memories and how you managed to arrive at this place where you can laugh it off?

Those scenarios were relentless, especially during my freshman year in high school. I finally hit the wall and realized I couldn’t stay in school anymore — not only was it intellectually a waste of time, but it was also actually unsafe. Being bullied wasn’t particularly amusing while it was happening; it was frightening.

As you mentioned, I was gay-bashed nearly to the point of death, something I graphically describe in Jimmy Neurosis. But it’s my general philosophy that’s it’s not useful to dwell on the darker stuff that occurred to me. It’s important to process and move on. Those experiences made me stronger. I’m strangely grateful for them now.

For a relatively small scene, there was an endless list of women and queers at the forefront of things, with bands like Suburban Lawns, The Mutants, Offs, The Screamers, Darby in Germs, and people like Kid Congo being in bands like The Cramps and The Gun Club. Was there any explicit dialogue around queerness within the community at the time?

No, not really. The word “queer” didn’t exist back then except as a derogatory term, but the original punk rock scene was very openly gay, lesbian, and transsexual. No group, class, belief, or skin color was excluded. Everybody was welcome. There simply wasn’t any talk of gay or straight or black or Mexican-American or white back then.

I guess I didn’t really realize what a golden age it was until after it was over and I witnessed California Punk, Part Two, also known as hardcore punk. That definitely was a more heterosexual, more male, and generally more white scene.

It’s may be dramatic to say, but it was a chilling chapter in the book when you describe returning to San Francisco from NYC to discover that Hardcore dominated the previously diverse, more experimental scene from which you sprung. Despite the homogenization that came with that era, labels like SST were still focusing on of all sorts of amazing bands — do you think they were inadvertently lending to this shift simply through housing bands that grew very popular like Black Flag, who at first glance seemed super macho?

Not really. It was just a natural transition. Punk rock had such a useful, core message—and the music was so great and new—that it eventually transformed and became a more business-friendly version of itself. The producers moved in. There were albums to be produced and there was money to be made—much more money than in the when it was a small grassroots movement and the freaks were running the show.

What’s key to remember is that in the Bay Area there were probably only around 500 people total who were involved in the scene in the beginning, and that’s a conservative estimate. It was tiny by later standards.

Why do you think that that sort of shift was so successful?

Because the social and political idea of punk rock is powerful. No one group or person owns it. Plus, it didn’t hurt that a lot of the music that came from the second wave of California punk was truly excellent — Black Flag, Flipper, and the Circle Jerks, for example.

You never felt any resentment towards that second wave of boy-oriented punk rock?

No, not at all. I just knew my time in the scene was over. I was already moving on to other things anyway.

Was there a palpable tension between these waves of punk that you describe?

Not really; not that I knew of.

Gay and queer communities rely on certain private spaces, like gay bars, or cruising areas or even various forms of code within which to communicate with one another to avoid commodification into the mainstream or heteronormative world. There are parallels here to the origins of the punk community. Can you talk about the difficulties that arise between maintaining these traditions while simultaneously seeking political visibility in terms of human rights that aren’t granted to more marginalised communities?

What I witnessed in the years following the assassination of Harvey Milk [San Francisco’s first openly gay elected politician who was killed in 1978] was a sort of commodification of gayness. I remember the first gay-oriented cable channel in the nineties. While I was definitely interested in it, I was also a little suspicious. I wondered if it was just another way to sell products.

Had gay equality become more about selling things than making sure that people didn’t nearly get killed when walking to a show on Saturday night in North Beach — like what had happened to me?

Was there a certain occasion that served as the genesis for your wanting to write this book at this point in your career?

Well, my punk rock years haunted me for decades. I’ve lead a rich and complicated life in the 40 years since then: I lived in Southeast Asia and India, I worked in the New York publishing world, I worked in Hollywood, both as a writer and as an on-camera food expert. I was in TV commercials. But whatever incarnation I was in or wherever I was, I would remember those years.

I knew for a long time that I wanted to do a project that revisited them but wasn’t sure what form that project would take. Eventually I realized I might have a memoir in me. From the time that I wrote the proposal for Jimmy Neurosis to the time that the book was published it was eight years! It was not a speedy trip.

But once I started writing the book, I realized that more than anything my goal was to give the teenage version of me a voice — he hadn’t had one up until then.

How did your origins in the punk universe inform your working experience in those more mainstream professional channels? Did it cause any conflict or did it help you navigate it in some way?

It showed me how to navigate my life in a much better way! I only realized this many years later, but everything I experienced during my wild teenage years prepared me for my adult life, all the hard times and all the good times. It showed me techniques and strategies for living in the world—techniques and strategies that have made the world a more positive place for me to live in now. I owe a great debt to those crazy, nascent years in the San Francisco punk scene.

In the book, the mother of your partner in crime, Blackie O, complains about the negative connotations of band names such as The Weirdos, Mutants and Suicide. Blackie O goes on to explain that this is a creative expression, and a way of being ironic “so you can feel better about how horrific the world really is.” In 2020 that sentiment seems more applicable than ever!

I don’t honestly see much difference between the late 1970s and 2020. I know a lot of young people in their teens and their early twenties nowadays, and even though they’re forty years younger than me, I feel like they’re super similar to the way I was at their age and their struggles in the world are familiar. There are great advancements these days, of course.

One of the things that the Internet has achieved is that it has allowed people who previously felt severely isolated a sense of connectedness. We didn’t have that in the seventies. But one thing I always remind younger people to do is to put aside the Internet and their smartphones and actually go out into the real world, not just stay trapped in the virtual world. The real world is so much more interesting and rewarding.

You’re working on a new series of cookbooks called World Food that will be published by Penguin Random House this fall. Do you see your punk rock voice in those works as well?

Punk rock showed me how to access the world. Right after the events written about in Jimmy Neurosis, I reunited with my dad. We took what was my first trip outside of the United States and went on a road trip from New Orleans to southern Mexico in his beat-up station wagon. We ate quesadillas toasted on clay grills. We slept in seedy colonial-era hotels. We walked through markets. All of that was seismic for me. It hooked me on travel for life.

In terms of how the punk rock impetus directly relates to the work I am doing now… Well, punk rock showed me how to be skeptical and how to explore. I guess it ultimately taught me how to be a journalist — it’s funny to think about it that way.

My core work for the last two decades has been about documenting and celebrating traditional global food and cooking, hopefully before the old ways get completely forgotten and replaced by the total corporatization of the world’s food supply. I want to celebrate what Grandma made for dinner before frozen food and industrial farming took over.

I think the world was a better place back then. But I don’t think it’s too late to change things.

— Q&A by Kevin Hegge (@theekevinhegge)

Jimmy Neurosis is available now in paperback. Follow James @jamesoseland and Jimmy @jimmyneurosis

Be the first to comment on "OMG, a Q&A with James Oseland"